When designing electrical products, safety isn’t just a feature—it’s the foundation. Protecting users from electric shock and fire risks requires a thoughtful, people-first approach. It’s not only about ticking compliance boxes, but about understanding how real people interact with equipment and ensuring those interactions are safe under all conditions, including faults.

Protecting Against Electric Shock

A common saying in the electrical world is: “It’s the volts that jolt, but the mils that kill.” This means voltage may cause the initial sensation, but it’s the current (measured in milliamps, or “mils”) that can be fatal. For example, a shock from a 230V outlet can be deadly if the current isn’t limited. That’s why many consumer devices are designed to operate at Safety Extra-Low Voltage (SELV)—below 50 volts AC—so they pose less risk even if something goes wrong.

Besides limiting voltage and current, other important protective measures include:

- Earthing (grounding) the equipment so dangerous currents don’t reach the user.

- Automatic power cut-off when a fault is detected.

- Physically blocking access to live parts, so users can’t touch anything dangerous even by accident.

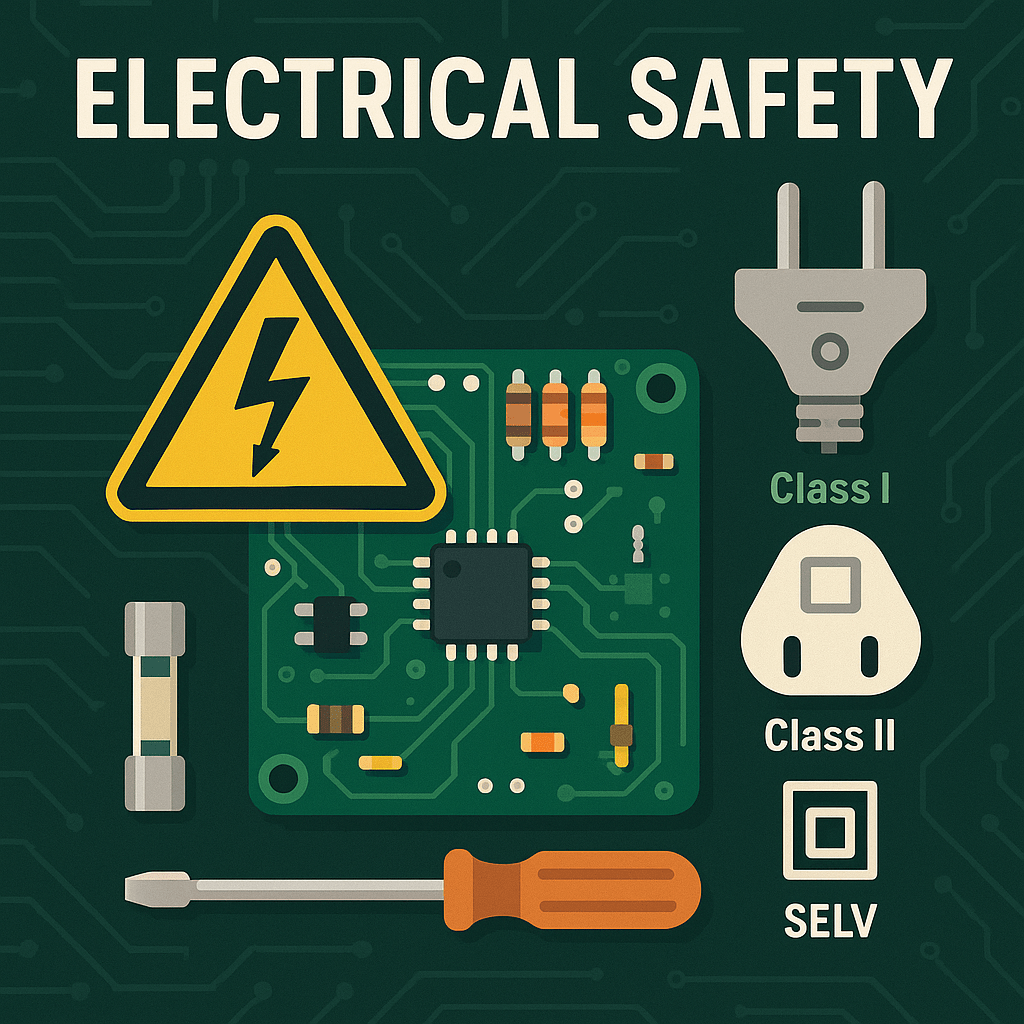

Understanding Safety Classes (IEC 60536)

To help manufacturers choose the right safety measures, the international standard IEC 60536 classifies electrical equipment into four safety classes, each with different protection strategies:

- Class 0: Relies only on basic insulation, with no connection to earth. It’s not acceptable in places like the UK due to the high risk.

- Class I: Uses both insulation and an earth connection. If the insulation fails, the earth wire carries the fault current safely away.

- Class II: Doesn’t use earthing. Instead, it relies on double or reinforced insulation, meaning there’s a backup layer of protection even if one fails.

- Class III: Operates entirely at SELV. It doesn’t generate dangerous voltages, so no special insulation or earthing is needed.

The Role of Insulation

Insulation is critical to preventing shocks. There are three main types:

- Basic insulation: A single layer that offers minimal protection.

- Double insulation: Adds a second, independent layer for fail-safe protection. This is often seen in products without earth connections.

- Reinforced insulation: A thicker, stronger single layer that provides the same protection as two layers.

When designing for safety, engineers ensure that even if one barrier fails, another remains to protect the user.

Making Dangerous Parts Inaccessible

A major part of electrical safety is making sure live components are physically out of reach. Openings in product cases must be too small for fingers or small objects like necklaces to slip through. Protective covers should require a tool to remove, and internal high-voltage sections should be clearly isolated and shielded. These design choices may seem invisible to users, but they’re critical for preventing accidental contact.

Durable, Safe Materials

Safety isn’t just about design—it’s also about durability. Insulation must resist wear and tear: drops, scratches, heat, humidity, and vibration. Materials like wood or paper, which absorb moisture, are not suitable. Designers also follow strict rules for creepage and clearance distances—how close two conductors can be without risk of sparking or breakdown.

Clear Labels and Safer Connectors

Safety continues even in how devices are labeled and connected. Equipment must be marked clearly and permanently, showing power ratings and connection points (like earth, live, and neutral). Fuseholders should display the correct fuse rating. Plugs and connectors must be designed so users can’t accidentally touch live pins, and when disconnecting, the earth pin should always disconnect last for safety.

Preventing Fire Hazards

Electrical devices must not catch fire—not during normal use, and not even during faults. That means:

- Preventing overheating.

- Using current-limiting devices like fuses and circuit breakers.

- Choosing flame-retardant materials—especially for circuit boards.

Fuses are cheap but can be misused, so they need clear instructions. Thermal cutouts and resettable circuit breakers are safer but cost more. Either way, the goal is to stop faults from turning into fires.

Leave a comment